The case of Attorney-General of Bendel State v. Attorney-General of the Federation & 18 Ors (1983) stands as one of the most defining constitutional law decisions in Nigeria’s legal history. It is a judgment that goes beyond mere interpretation of revenue allocation; it boldly redefined the limits of federal power, the autonomy of state governments, and the core principles of Nigerian federalism under the 1979 Constitution.

At a time when Nigeria’s federation was still finding its constitutional balance, this case boldly answered a fundamental question:

Can the Federal Government of Nigeria unilaterally withhold or administer funds constitutionally belonging to a State?

This dispute between the Attorney-General of Bendel State and the Federal Government not only tested the boundaries of constitutional power but also reaffirmed the sacred doctrine of fiscal federalism, ensuring that no arm of government could usurp the financial autonomy of another.

BACKGROUND AND FACTS OF THE CASE AG BENDEL v. AG FEDERATION

The Attorney-General of Bendel State, relying on Section 212 of the 1979 Constitution, invoked the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Nigeria to challenge the constitutionality of certain provisions in the Allocation of Revenue (Federation Account, etc.) Act, No. 1 of 1982.

The National Assembly, acting under Section 149(3) of the 1979 Constitution, had enacted this law to provide a formula for the distribution of revenue accruing to the Federation Account among the Federal, State, and Local Governments.

However, two controversial sections of the Act became the crux of this litigation:

Section 2(1)created a fund to be administered by the Federal Government for the amelioration of ecological problems in any part of Nigeria.

Section 2(2) provided for another fund to be administered by the Federal Government for the development of mineral-producing areas.

Additionally,Section 6(1) established a Joint Local Government Account Allocation Committee for each state, with specific administrative duties imposed on state officials.

The plaintiff (Bendel State) contended that these provisions were unconstitutional because:

1.They allowed the Federal Government to withhold and administer parts of funds constitutionally due to the States.

2.They imposed duties on State functionaries, contrary to the principle of state autonomy under the federal structure.

3.The National Assembly had acted ultra vires (beyond its powers) by creating funds without prescribing a proper formula for distribution.

After failed attempts to resolve the matter administratively, Bendel State brought the case before the Supreme court. Due to its national importance, all State Attorneys-General were joined as defendants.

ISSUES BEFORE THE COURT IN A.G-OF BENDEL STATE v. A.G-FEDERATION & 18 Ors(1983)

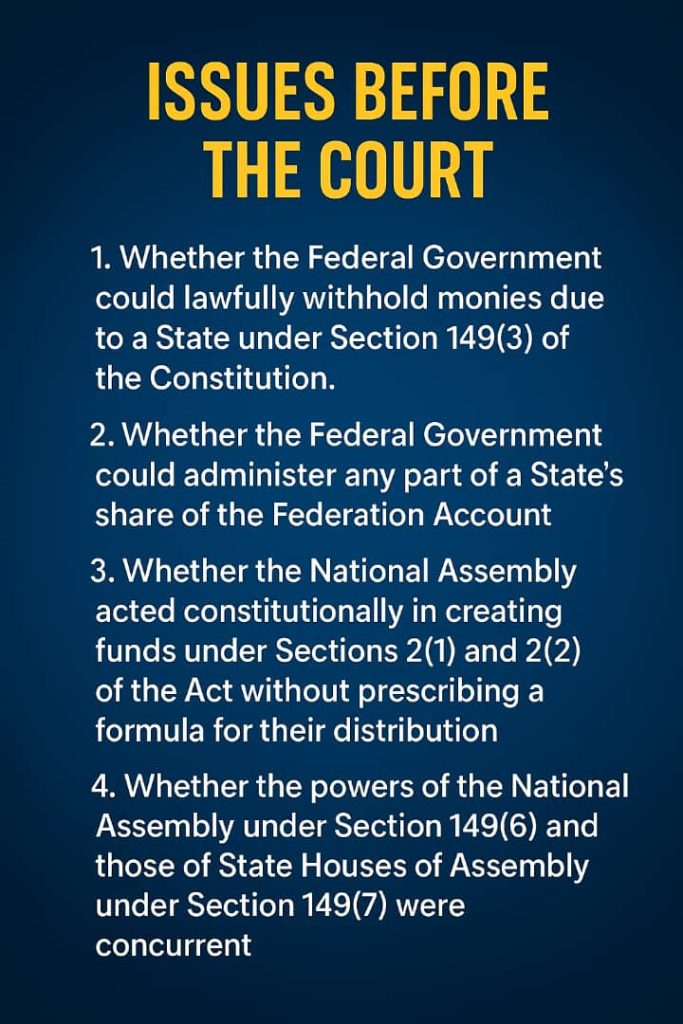

The Supreme Court was invited to determine several critical issues, among which were:

1.Whether the Federal Government could lawfully withhold monies due to a State under Section 149(3) of the Constitution.

2.Whether the Federal Government could administer any part of a State’s share of the Federation Account.

3Whether the National Assembly acted constitutionally in creating funds under Sections 2(1) and 2(2) of the Act without prescribing a formula for their distribution.

4.Whether the National Assembly could validly impose duties on State officials.

5.Whether the National Assembly had powers to legislate regarding allocations to Local Government Councils.

6.Whether Section 6(1) of the Act establishing the Joint Local Government Allocation Committee was constitutional.

7.Whether the powers of the National Assembly under Section 149(6) and those of State Houses of Assembly under Section 149(7) were concurrent.

Judgment of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgment delivered by a full panel consisting of Sowemimo, Irikefe, Bello, Idigbe, Obaseki, Eso, and Uwais JJ.S.C., gave a landmark interpretation of Sections 149 and 212 of the 1979 Constitution.

1. On the Autonomy of State Governments and Federal Control

Justice Idigbe, J.S.C., emphasized that once the Federation Account has been divided among the three tiers of government, the States collectively become the absolute owners of their respective shares.

“In a Federal set up, it is necessary that each of the two tiers of Government is reasonably autonomous — each having a separate existence and remaining independent of control by the other.”

The Court held that the Federal Government’s attempt to administer or retain any portion of funds due to States under the guise of ecological or mineral funds was unconstitutional.

2. On the Withholding of State Funds

Justice Irikefe, J.S.C.,was direct and unequivocal in his reasoning:

“By no stretch of the imagination can Sections 149(2), (3), and (4) of the Constitution be construed as vesting in the National Assembly powers to enable the Federal Government hold back any proportion of funds comprised in the percentage already distributed to a State.”

Thus, the Supreme Court declared that the Federal Government had no power to withhold or administer any part of the State’s share

3.On the Creation of Special Funds

The Court struck down Sections 2(1) and 2(2) of the Allocation of Revenue Act, No. 1 of 1982, as unconstitutional,holding that they were not authorized by Section 149(3) of the 1979 Constitution.

Justice Eso, J.S.C.,captured the spirit of the Court’s reasoning in a dictum that has since become a constitutional classic:

“On an ordinary literal interpretation of Section 149 of the 1979 Constitution, it is plain beyond doubt that any enactment that gives any portion, however so small, of the percentage due to the States to any person, project, organisation, or institution other than the States, is void and unconstitutional.”

4. On the Ecological Problems and Federal Expenditure

Justice Sowemimo, J.S.C.,acknowledged that ecological challenges were unforeseen and could arise anywhere in the federation, but insisted that funding for such emergencies must come through proper constitutional means:

“Whenever ecological problems occur, expenditure on them cannot be estimated as they are unforeseeable. Therefore, no sums of money can be estimated under an appropriation bill. The Federal Government must have recourse to expenditure under an Appropriation Act or through Contingencies Fund as provided by the Constitution.”

5. On the Imposition of Duties on State Functionaries.

The Court examined whether the National Assembly could impose administrative duties on State officials under Section 6(1) of the Act. It held that the Constitution itself allowed both Federal and State Legislatures to impose duties on each other’s functionaries, citing Sections 150(b), 195(4), 250(1), and 251(3) of the 1979 Constitution.

Thus, Section 6(1) of the Act establishing the Joint Local Government Account Allocation Committee was held to be constitutional and valid.

6. On the Nature of the Federation Account

In one of the most illuminating declarations on fiscal federalism, the Court held that the Federal Government’s position in maintaining the Federation Account was that of a trustee.

“The Federal Government, in maintaining the Federation Account, acts as a trustee for the State Governments and the Local Government Councils. It must render accurate and regular accounts to the beneficiaries.”

This reaffirmed the fiduciary responsibility of the Federal Government to maintain transparency and accountability in revenue distribution.

RATIOS ESTABLISHED IN A.G-OF BENDEL STATE v. A.G-FEDERATION & 18 Ors(1983)

1.Under Section 149(3) of the Constitution, amounts standing to the credit of State Governments in the Federation Account must be distributed among them. The provision is mandatory.

2.The Federal Government cannot retain or administer any portion of a State’s share without the latter’s authorisation.

3.The National Assembly, by creating special funds under Sections 2(1) and 2(2) of the Act, acted ultra vires and those provisions are null and void.

4.Section 6(1) of the Act, establishing the Joint Local Government Account Allocation Committee, is valid and constitutional.

5.The National Assembly and State Houses of Assembly have concurrent legislative powers under Sections 149(6) and (7) of the Constitution.

6.The Federal Government, as trustee, must render accurate and periodic statements of all monies paid into the Federation Account to all States.

Indeed,the decision in A.G. Bendel State v. A.G. Federation (1983) remains a cornerstone of Nigerian constitutional and fiscal federalism. It set out the boundaries of federal power and reaffirmed the financial independence of States.

The case further strengthened the principle of separation of powers within a federal framework, ensuring that the National Assembly cannot arrogate to itself functions not granted by the Constitution.

To this day, the judgment is frequently cited in constitutional law discourse concerning revenue allocation, fiscal autonomy, and federal accountability in Nigeria and overall supremacy of the constitution.

YOU MAY CHECK OTHER CASE ANALYSIS BELOW:

BRONIK MOTORS LTD. v. WEMA BANK LTD. (1983) Full Case Summary

A.G of the Federation v. A.G of Imo State (1982) FULL SUMMARY